By Joel Makower

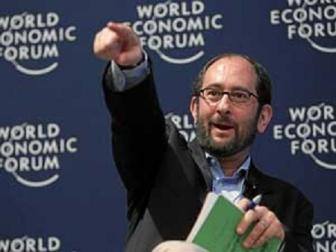

I met Aron Cramer in 1995, weeks after he joined BSR, the San Francisco-based global network of more than 250 member companies working on sustainable business strategies and solutions. He went on to open the organization’s Paris office in 2002 and became BSR’s president and CEO in 2004. I’ve had the good fortune of working with BSR in a number of capaci ties since its founding in 1992, and have watched Cramer emerge as one of the world’s most articulate thinkers on the opportunities and challenges that lie at the intersection of business and sustainability.

On the occasion of the paperback publication of his book, Sustainable Excellence, co-authored with Zachary Karabell — and in the run-up to next week’s 2011 BSR Conference, November 1-4 in San Francisco — I caught up with Cramer to find out how corporate responsibility has changed since we last talked a year ago, the impacts of the economy on sustainability and what the public expects from business these days.

Joel Makower: Let’s talk about what’s changed over the past year or so, and where things are going. For starters, what’s the impact of today’s economy on companies’ search for sustainable excellence?

Aron Cramer: Well, the prospect of an extended period of economic stagnation is underlining and reinforcing some aspects of sustainable excellence, and it’s reorienting some of them. Some of the things that remain as true — in fact, I’d say are more true in light of a weak economy — are the importance of innovation to sustainability, because every period of economic retreat shows that innovation is central to companies’ forward progress.

Those companies that stop investing in innovation during bad times stay in bad times. And those that redouble their efforts come out more quickly and are the champions that can take advantage of a rebounding economy. And because the world’s biggest challenges continue to be linked to sustainability, this period of stagnation only reinforces the need for companies to look at ways they can develop new products, new services, new partnerships that will allow them to turn sustainability into a business opportunity. So that’s been reinforced, and I think it will only be more true in the years ahead.

Makower: It seems to be harder to look to business as a savior at the same time that the private sector''s standing is so low.

Cramer: One of the ways that the agenda is absolutely changing is that there is economic vulnerability in the West on an order of magnitude that we’ve not seen for decades. And that is changing the sustainability agenda because the level of trust in business is very, very low. People feel as though their needs may not be taken care of.

We’ve got chronic unemployment throughout the West and no prospect that that’s going to turn around anytime soon. And for the first time since the Rio Summit in 1992 — in the modern history of sustainability — we’ve got a large percentage of the western population that feels as though they are on the edge. That’s why we’ve seen the Occupy Wall Street movement gain some steam. I think this means that questions around executive compensation, around transparency, around governance, around what a company is doing with respect to lobbying, the level of profits that some sectors — particularly the financial services sector and the energy and extractive sectors — these are all going to be getting greater scrutiny.

So if the agenda has been defined along environmental lines in many ways over the last few years, the social and economic side is becoming much more important. It’s something that companies overlook at their peril.

Makower: One of the things that’s changed in the past year is this citizen uprising called Occupy Wall Street. As we’re speaking we’ve got a tent city outside the GreenBiz office window in Oakland City Hall plaza. What do you think the connection is to companies and sustainability? What do you think the response if any should be by companies to this movement?

Cramer: The meta-question is whether or not the business sector and individual companies are defining their goals in sync with society’s goal. What’s interesting is this comes from the political left, but there are similar calls and concerns from the political right. People have concluded that business is out of sync with society.

I think that is a very dangerous place for business to be because that will lead to a much more reflexive anti-business approach that may end up throwing the baby out with the bathwater. That can lead in democracies toward regulation that may be designed to diffuse anger rather than address good long-term planning, and I think that’s a big risk. It also means that business has a big job to do to help the public understand that long-term investments, which of course are crucial to building a sustainable economy, remain important even at a time when short-term pain is acute.

So it’s a tall order for business. But I think if business doesn’t meet this challenge, it means that business’s position overall is going to be undermined. And the opportunity to make the kinds of long-term investments in infrastructure, in new transportation systems, in lower-carbon forms of energy, in a food system that delivers good nutrition and health — all of these things are going to be very, very hard to accomplish. We all lose if we don’t accomplish those things.

Makower: So, at the same time that we have this movement from both the Left and the Right pushing business to act in some new ways, we have these movements that are lessening, seemingly lessening the urgency for action on climate change. How do those reconcile those and, again, what’s the business response?

Cramer: I think it is one of the most negative dimensions of the current political debate, at least in the United States. Businesses have largely stayed committed towards their actions to adapt what they do for an era when climate change is a bigger part of our reality. What businesses have not been doing is shifting the political debate in the United States and to some degree elsewhere such that the commitment to addressing climate change remains strong.

I think business has to some degree been a little less vocal about the need for concerted action in the political sphere in order to develop the kinds of systemic approaches that are necessary to make real progress. And after all, if anything, the climate crisis is accelerating, something Al Gore will of course be speaking about at the BSR conference. All the science suggests that warming is accelerating and we don’t have a public debate that is reflecting that.

Makower: What are some of the other issues on the rise over the past year?

Cramer: There’s a much greater sense that water is an issue and more and more companies are developing policies on water. Waste has come into the mainstream in a sense. You see this in a variety of ways, from the recent announcement of the partnership between Waste Management and Recyclebank to the number of companies in the food sector that are taking on the question of food waste.

Frankly, I’m surprised that the question of waste isn’t getting more attention. In the United States, where one-third of the food and one-third of the energy that’s generated in this country is essentially wasted, you would think that in times of economic distress that that would become a much stronger point of action because that also means that we’re throwing away one-third of the money that we spend on those things. That’s true for households and for companies. I would argue that this is actually one way to build more momentum with the average person, the average household, with all of us as consumers, because we’re very wasteful. In times of economic difficulty, waste is not only an environmental problem. It’s a big economic problem as well.

Makower: It seems that some of this lies in the responsibility of consumers, to be pushing businesses and politicians in this direction. Do you see any opportunities for business to engage with consumers on these fronts?

Cramer: Consumers continue to be schizophrenic about all of these questions. The polling data show that the average person is less concerned about climate change and also believes that it is a growing threat. So I think we’ll all grow old waiting for consumers to have a unified state of mind on all of this.

The opportunity for companies is to make better products that deliver better outcomes that save people money. To some degree, I think the most ingenious summing up of sustainability that I’ve heard comes from Walmart’s tagline, Save Money, Live Better. That should be the mantra for all of us who work on sustainability because I believe that better products, whether it’s a more efficient car or food that comes with less waste and is more nutritious and also tastes good — those are things that help us live better and also save money.

So the opportunity for companies to do that is very strong. We see lots of companies looking at this, from Unilever to Nike to Best Buy — all thinking about reconfiguring the products that they’ve sold traditionally, but also coming up with new products that help us manage energy in our home better, manage our own health and well-being, manage the intake of calories in the food that we buy. Those are all things that can help us live better lives and in many cases will also result in our spending less money.

Makower: I’m still unclear what we call this movement. Once upon a time it was corporate social responsibility; maybe it still is. “Sustainability” now seems to be rising. And there’s “green” and “citizenship” and everything else. What’s your take on how we should harmonize the language?

Cramer: The big idea here is lasting prosperity for all the world’s people. That ultimately is the social outcome, the environmental outcome that we want to achieve. For companies, I would say it’s sustainable excellence — the notion that companies can compete best in the marketplace when they’re thinking about sustainability as a crucial part of what they do. And that they achieve sustainability when they apply the same principles of excellence to that aspect of their work as they do to product development and marketing and logistics.

For me, sustainable excellence is the term that I think resonates well with business. For the consumer, this is all jargon and is not something that’s widely understood. I think you have to speak almost at a micro level to consumers to help them understand how they’re getting better outcomes — that is as much about consumer delight as it is about sustainability or corporate responsibility or shared value or whatever term you want to use.

So, I think it depends on who you’re talking to. At a macro level, we’re talking about sustained economic prosperity globally. For companies, I think sustainable excellence sums it up well. And for consumers, let’s go and give them great outcomes that also happen to deliver great outcomes with respect to the environment and access to basic needs and, hopefully, the kinds of delight that most consumers want.

Makower: I guess consumers want sustainable excellence, too, in terms of prosperity in all the ways you’ve described it. It’s just a matter of how to explain to them that this is what they might be getting.

Cramer: I think that’s right: ultimately consumers want excellence. I think the sustainability part is something that goes to their definition of excellence or quality or delight. It really does have to be integrated in that way because the number of people who lead with sustainability in their choosing and using products remains quite small and is likely to remain small.

Makower: I have a sense that the public is looking for corporate heroes. Do you agree?

Cramer: I think the public is looking for heroes right now, certainly on the business side. When we think about heroes in any walk of life, we think of people who — I guess Steve Jobs comes to mind. Someone who breaks the mold, who creates something that’s different, who acts according to a set of principles that they understand. So yes: I think the public is looking for heroes in the business world.

This is why the death of Steve Jobs brought such an outpouring of support and affection. And green business heroes I hope are emerging. If the 2010s are remembered as a time when those were the kinds of heroes we saw from the business world, I think that the 2020s will look a lot better.

Article courtesy of greenbiz.com