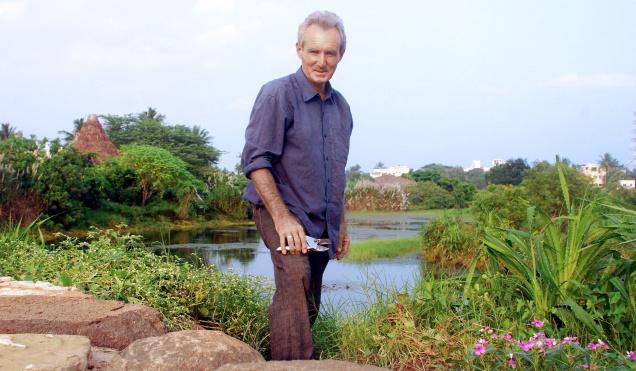

Joss Brooks is a man difficult to catch up with. It was raining, but he walks up and down the restored mounds and the new “cottages” of Adyar Poonga, explaining the toil behind the transformation. I want the sun shining — on his past. “The story is about you,” I tell him. . He agrees. Reluctantly.

Born in Tasmania — t he Australian state was the first to have a Green Party — Joss grew up watching an environment movement. He remembers seeing activists protesting against building of dams and destruction of rivers and forests by chaining themselves to bulldozers, sitting in trees and digging themselves into the ground. He absorbed an indelible lesson: there was an urgent need to gain skills to protect what was left of Nature and to restore what lay wasted.

He chose to study history, philosophy and French in Western Australia, before he left the country. He travelled to Central America, experienced the student upsurge in the Paris of the 1960s, and eventually landed in Ramana Maharishi's ashram in Thiruvannamalai. “I found peace and beauty in the traditional culture and indigenous vegetation of South India,” he says. “I've lived on the banks of the Ganges and in a Himalayan Kumaoni village for six months before discovering Mother and the young community of Auroville.”

PROTECTING NATURE

He also discovered his love for protecting Nature, and learned skills for wasteland restoration. Along with co-ashramites he started the long process of healing what looked like forgotten land. In the 1970s, it was a tough call. Using wooden ploughs and bullock carts they planted trees, grew bio-fences, dug wells, erected a windmill and built earthen bunds to stop erosion by rainwater. They brought back the grass cover and grew food crops, while living off the land frugally. Through all the hard work of greening Auroville and the arid Pitchandikulam where he lives, he was guided by Pondicherry's Mother, he says. “She told us that the spirit of the forest and wilderness were there to help if we could connect with it. Mother encouraged us to imagine the possibility of what could be.”

Pichandikulam, his baby, is now a tropical, dry, evergreen forest with 400 medicinal plants. Nattu vaidyars teach herbal medicine in his Bio-resource Centre, school children and others paint and sculpt images of local flora and fauna. The Nadukuppam school his team adopted several years ago has an environment centre, water supply, toilets and solar-powered water treatment systems. The kids have planted a vegetable garden in the grounds, women grow spirulina and prepare herbal medicines for cattle camps, and men increasingly do organic farming.

Adyar Poonga is another restoration story. Once he had the contract (“no one else applied!”), his team (Pitchandikulam Forest Consultants) removed 60,000 tons of garbage and rubble from the site. He created waterbodies, and around them planted 90,000 seedlings of 172 indigenous species on 300 tons of laterite soil brought from Auroville. Under his brand of restoration ecology, the city dump has had an unimaginable make-over. It has an Environmental Education Centre, and a children's interactive area. The nursery has specimens for medicinal plants, models for solid-waste management and renewable energy. Standing stones have been painted with beaks and bird feet. The Poonga has breathing space for insects and animals to breed and colonise, and plants to establish themselves.

Joss sees Adyar Poonga as an environment-education tool. “We started organising exhibitions and visits for children. We talked to the people around not to throw garbage. If the water flowing into the Poonga is to be clean, streets have to be clean, garbage has to be separated. It is a residential area, so the involvement of local people is essential,” he says.

“I am not a scientist,” he claims, so think of him as one whose dreams are painted a bright green. In his “magical process”, the eco-restoration will leave the tidal water coming in under Santhome causeway sparkling clean. Children will swim in the Buckingham Canal and people will cycle to work along a sweet smelling Otteri nullah. “Just imagine!” he says, “Chennai could be a city of clean waterways and lakes.”

He was thrilled to spot a painted stork that came calling for the first time, on his birthday. Species of animals and birds are regular visitors now. He says proudly, “Here's a wild space in the middle of the metropolis, giving a bit of Chennai back to Mother Nature.”

Article courtesy of thehindu.com