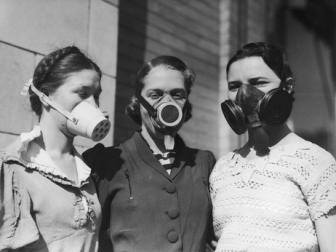

By RANDALL CURREN Today we have a guest post by Randall Curren, chair of the Philosophy Department at the University of Rochester. He holds a secondary appointment in the university''s Warner School of Education. Curren has written extensively on the philosophical issues surrounding education and sustainability. —Adam Frank Talk of sustainability is fashionable and more than a little free wheeling; but it''s not just a fad. At its core, the language of sustainability is a way of referring to the long-term dependence of human and non-human well-being on the natural world, in the face of evidence that human activities are altering, damaging, and disrupting the natural systems on which we and other species fundamentally rely. What unsustainability implies is that humanity is collectively living in such a way as to diminish opportunities to live well in the future. The preservation of opportunities to live well is the central value at stake in sustainability. Sustainability ethics may consequently be defined as the domain of ethics and ethical inquiry pertaining to every sphere and aspect of human activity as they bear on the capacity of natural systems to provide opportunities as good as the ones available now, indefinitely into the future. The extent and quality of opportunities rest on the abundance of natural capital. Actions, practices, policies and systems that diminish the abundance of natural capital are a primary concern of sustainability ethics. The first principle of sustainability ethics is: Do not diminish natural capital. A second principle arises from the fact that opportunities to experience the natural world are important to human well-being but not captured by the idea of natural capital: Do not diminish satisfying opportunities to experience nature. Our actions diminish natural capital and opportunities to experience nature incrementally, globally and often without any identifiable victim, making it hard to know what would count as full compliance with these principles. It feels better to do what one can to reduce consumption and waste, but how much is enough? How much difference will the voluntary actions of individuals even make? The best answer to such questions is that changing the way we individually live, and doing so voluntarily before needed policy reforms are in place, is essential. Without this, it is very unlikely that our leaders will perceive a window of political opportunity to negotiate needed treaties and enact suitable laws. We need such treaties and laws because individual actions will not suffice without global coordination and regulatory mechanisms to set safe aggregate limits for greenhouse gasses and other burdens on the earth''s natural systems. The translation of environmentally safe overall limits into enforceable limits on what individuals may do is the only efficacious means by which we can collectively determine what is and is not sufficient personal restraint. To say this is to affirm that a fundamental burden we all bear — individual, institutional and government actors alike — is to seek fair terms of cooperation in living sustainably. Our unsustainable energy and transportation systems already have damaging global reach, including an estimated 150,000 deaths each year attributable to climate disruption. It is undeniable that we are already interacting with others around the globe in ways that damage their interests. We are doing this while hesitating to negotiate a mutually agreeable climate treaty, as well as other environmental protection treaties. This hesitation is itself morally objectionable. It is wrong to act in ways that impose risk and harm on others and to refuse to face them and negotiate reasonable limits on those impositions. Facing them as equals and specifying the details of our moral relations with each other in a body of common law is a requirement of basic moral respect. A third principle of sustainability ethics is, thus: Seek fair terms of cooperation conducive to sustainability. Actors whose actions affect each other are obligated to cooperate in negotiating fair terms of cooperation in living in a manner that is collectively sustainable. Fair terms of cooperation would undoubtedly define not only the terms of shared sacrifice in achieving a sustainable human footprint, but also what will constitute wrongful impositions of environmental risk on identifiable populations and jurisdictions. Transparency is a condition of good faith negotiations and a foundation to democracy. So a fourth principle of sustainability ethics is: Do not obstruct transparency with regard to sustainability. Obstruction of transparency is apparent in the success of industry front groups in misleading the public about such matters as the strength of scientific consensus regarding anthropogenic climate change. Especially when the stakes are high — as they are with respect to sustainability — we should acknowledge that it is a simple matter of prudence to ensure that our institutions promote transparency, or the efficient discovery and dissemination of truths important to our interests. Hence, a fifth principle: Societies and their and governments should create and sustain institutions and systems that are conducive to sustainability and conducive to transparency with respect to sustainability. Misleading people about the environmental impact of products and business practices may enhance profitability. It may also serve to induce a risky reliance on vulnerable systems, subjecting people to risks they would otherwise not face. This too is unethical, and its wrongness may be captured in a sixth principle: Do not induce or cause anyone to be in a position of fundamental reliance on vulnerable systems or resources — systems or resources that cannot be relied on without exposure to systemic risk to their fundamental interests. This principle of detrimental reliance captures what is most ethically troubling about the human context of the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. In that environmental disaster homesteaders were induced — by the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 and the railroads and prairie state senators who promoted it — to farm a region unsuitable for farming, largely destroying the grasslands constituting North America''s second-largest ecosystem. In the drought of the 1930s that followed, the unanchored soil was gathered by winds into dust storms 10,000 feet high, or more, blinding and suffocating cattle, obliterating roads and dropping thousands of tons of dust on cities hundreds of miles away. A quarter of a million people, people who had been induced to settle and farm a region that had previously supported only a few hunting camps and native-American villages, fled, leaving behind 100 million acres in ruin. The events of the Dust Bowl illustrate the peril in failing to grasp that the opportunities we value are, in the long run, much more dependent on environmental preservation than we may be led to believe. If the 2005 Millenium Ecosystem Assessment is correct in finding that 60 percent of the world''s ecosystems are in decline owing to overuse, the long run is at hand. The time for ethical clarity about sustainability is also at hand. Article courtesy of npr.org