By JULIA MOSKIN

LAST week in Chelsea, Mich., as people wilted and vegetables flourished in the intense heat, Anne Elder ran through some of he

r favorite summer ingredients: pearly garlic “rounds” that flower at the top of the plant in hot weather, the spreading leaves of the broccoli plant, yellow dandelion flowers that she dips whole into batter and deep fries.

“When kids visit the farm, we give them cornstalks to chew,” she said. Like sugar cane, the stalks contain sweet juice.

For Ms. Elder, who runs the Community Farm of Ann Arbor, the edible vegetable begins with the sprouts and does not end until the leaves, vines, tubers, shoots and seeds have given their all.

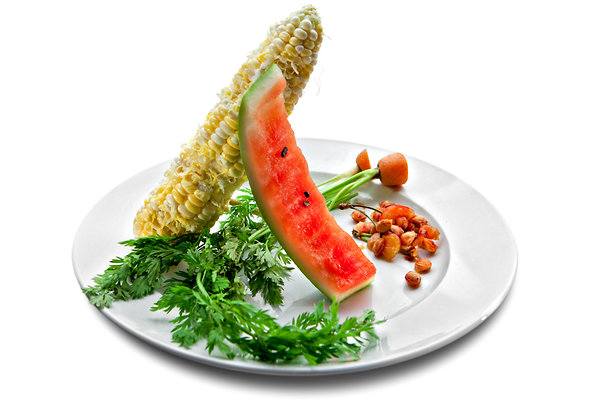

If home cooks reconsidered what should go into the pot, and what into the trash, what would they find? What new flavors might emerge, what old techniques? Pre-industrial cooks, for whom thrift was a necessity as well as a virtue, once knew many ways to put the entire garden to work. Fried green tomatoes and pickled watermelon rind are examples of dishes that preserved a bumper crop before rot set in.

“Some people these days are so unfamiliar with vegetables in their natural state, they don’t even know that a broccoli stalk is just as edible as the florets,” said Julia Wylie, an organic farmer in Watsonville, Calif. The produce she grows at Mariquita Farm is served at Bay Area restaurants like Delfina, Zuni Cafe and Chez Panisse.

At some large farms, she said, only the florets are processed for freezing or food service; the stems are shredded into the chokingly dry “broccoli slaw” sold in sealed bags at the supermarket.

(A much better way to treat broccoli stalks: cut off and discard the tough outer peel, shave what remains into ribbons with a vegetable peeler, scatter with lemon zest and shards of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese: all the pleasure of raw artichoke salad with half the work.)

Mariquita Farm also runs a flourishing Community Supported Agriculture (C.S.A.) program and sells at farmers’ markets, where, Ms. Wylie said, she has become expert at holding shoppers’ hands when it comes to stem-to-root cooking. She reminds them that even the thick ribs of chard, beets and other greens soften with braising (most kale stems, though, are too fibrous to eat). She encourages them to cook the leaves that sprout from the tops of radishes (they have a delicious bitterness) and offers a traditional French method of baking fish at high heat on a bed of fennel stalks.

Among her favorite neglected greens are the big, sweet leaves that grow around heads of cauliflower — leaves that supermarket shoppers never see and recipes never call for. She cuts them across the ribs, then sautés them with minced onion.

“It’s like a silky version of a cabbage leaf, with a hint of cauliflower,” she said.

At this time of year, cooks around the country haul home full bags from the farmers’ market or a weekly box from a local farm but also wonder how to make the most of their produce. Eating more vegetables, being spontaneous in the kitchen and celebrating the season are the aspirations that lead people to join C.S.A.’s. But many find that they don’t know what do to with boxloads of melon, tomatoes, onions and leafy greens, not to mention their stalks, tops, peels and stems.

“I joined a C.S.A. because I wanted to be frugal and I thought it would force me to be creative in the kitchen,” said Megan Smith, a learning specialist in Brooklyn. “But it generated a huge amount of work and all this debris.”

Much of what is tossed out is edible, but not everyone greets the opportunity to recycle food scraps as an exciting food adventure.

“When you mention using them for stock, that’s when people start to roll their eyes,” said Ronna Welsh, a cooking teacher in Park Slope, Brooklyn, who chronicles her adventures with chard stems and watermelon rinds on her Web site Purple Kale Kitchenworks, in a column called “Otherwise, Trash.”

Her students are the kind of home cooks who make the extra effort to go the farmers’ market and support local agriculture, she said, but whose schedules and lack of skills cause them to feel stressed by a refrigerator full of raw ingredients.

Ms. Welsh likes to generate recipes for trimmings, she said, because using up everything satisfies some of the same urges that fuel the desire to be a better cook.

“When you spend $40 at the Greenmarket, the pressure starts right there,” she said. “You feel more invested in the carrots you buy from the farmer than the ones you buy at Key Food. You feel sentimental about them, you have more respect for them.”

Ann Arbor, with its thriving farms, gardens and greenmarkets — including a new one this summer that is held in the evening so that working people can shop — is a fertile source of stem-to-root ideas.

“People know that nasturtium flowers are edible, but the leaves are also great salads and the seed pods, if you pickle them, make a wonderful substitute for capers,” said Kevin Sharp, an outreach manager at the People’s Food Co-op there, one of the oldest in the country.

He substitutes the palm-size leaves from stalks of brussels sprouts in recipes that call for collard greens, cooks the leaves and shoots of sweet potatoes and battles a bumper crop of asparagus by making a sweet relish from the woody ends.

Lindsay-Jean Hard, who works at a new farm-to-table Web network called Real Time Farms, said that she chops the leaves atop celery stalks to make a pungent, fluffy celery salt.

Last year, hundreds of homeowners around Ann Arbor joined a local 350 Gardens Challenge, a global climate-change initiative that includes “visible food production” (like a garden in an urban front yard) as one of its engines for sustainable food.

One of those homeowners, Erica Blom, a graduate student who says she eats everything from apple cores to potato peels, especially if they come from her own garden, has embraced the slight bitterness of her homegrown carrot tops, mincing them as a garnish like parsley and using them in salads.

Andrea Reusing, a stem-to-root chef, hammers cherry pits for the panna cotta she serves at her restaurant, Lantern, in Chapel Hill, N.C.

Modern chefs have long embraced a nose-to-tail approach to meat, but recently they have been looking at the plant kingdom with a predatory eye. One of the most adventurous is Andrea Reusing of Lantern in Chapel Hill, N.C.

“It came from a curiosity about flavor, more than a need to use things up,” she said, referring to stem-to-root recipes she has tinkered with. “But of course that’s a benefit, and something our ancestors were very good at.”

She has infused wine with peach leaves, toasted the seeds of watermelons and taken a hammer to cherry pits, cracking them open to unleash the kernels’ sweet almondlike perfume into panna cotta. The recipe is included in Ms. Reusing’s new book, “Cooking in the Moment.”

(But as good as it is, this dessert should be eaten in moderation. Cherry pits, like peach leaves and apple seeds, contain minute amounts of cyanogens, compounds that can produce the poison cyanide. Other plant parts can also contain small amounts of toxins, so be cautious when eating them. The central number for the American Poison Control Centers is 800-222-1222.)

Ms. Reusing spends a lot of time prowling farms in North Carolina, where, she said, she finds all sorts of renegade vegetable specimens. She particularly relishes the strange shoots that emerge when a garden has bolted from too much heat: cilantro flowers, broccoli seed pods and tough lettuces that cry out for creamy, rich dressings and bacon-fat vinaigrettes.

Her cooking often combines Southern farmhouse tradition with the flavors of Japan, Korea and China, rich sources of stem-to-root traditions. She buys from farmers who grow Asian varieties of turnips, soybeans and radishes; she has salt-cured whole daikons, pickling the white flesh and salting the greens with chiles. The leaves of the wasabi root, she said, have an oily, mustardy kick: she slices them thinly to use as a garnish for a Japanese-inflected pot-au-feu.

Other chefs are redrawing the sometimes arbitrary lines between vegetables, fruits and weeds. At Jeni’s Splendid Ice Cream in Columbus, Ohio, Jeni Britton Bauer “milks” the first corn cobs of the local harvest, adding the sugary liquid to her basic ice cream mixture, and then swirls the buttery results with tart berries.

John Shields, the chef at Town House in Chilhowie, Va., festoons plates with chickweed and makes juice from wild grass. Last summer he harvested a crop of green strawberries, curing them in salt and sugar so he could serve them as dessert with soft drifts of whipped cream, cucumbers and marshmallow.

For Mr. Shields, stem-to-root cooking is a means to an avant-garde end. He worked in Chicago at Alinea and Charlie Trotter’s before making his way to Chilhowie, in a part of southern Virginia pressed up against the Appalachian hills. The lush wild and farmed land around the restaurant is, he said, the main reason for restaurant’s location, with unexpected vegetal pleasures that even the lushest urban farmers’ market cannot provide.

“I picked the flowers and shoots from the green bean plants at my farm this morning, and I am going to work with their sweetness,” he said. “In my kind of cooking, I wouldn’t really know what to do with green beans.”

At Your Disposal

Before you throw away your vegetable trimmings, consider some alternative uses:

CARROT, CELERY AND FENNEL LEAVES Mix small amounts, finely chopped, with parsley as a garnish or in salsa verde: all are in the Umbelliferae family of plants. Taste for bitterness when deciding how much to use.

CHARD OR COLLARD RIBS Simmer the thick stalks in white wine and water with a scrap of lemon peel until tender, then drain and dress with olive oil and coarse salt. Or bake them with cream, stock or both, under a blanket of cheese and buttery crumbs, for a gratin.

CITRUS PEEL Organic thin-skinned peels of tangerines or satsumas can be oven-dried at 200 degrees, then stored to season stews or tomato sauces.

CORN COBS Once the kernels are cut off, simmer the stripped cobs with onions and carrots for a simple stock. Or add them to the broth for corn or clam chowder.

MELON RINDS Cut off the hard outer peels and use crunchy rinds in place of cucumber in salads and cold soups.

PEACH LEAVES Steep in red wine, sugar and Cognac to make a summery peach-bomb aperitif. (According to David Lebovitz’s recipe, the French serve it on ice.)

POTATO PEELS Deep-fry large pieces of peel in 350-degree oil and sprinkle with salt and paprika. This works best with starchy potatoes like russets.

YOUNG ONION TOPS Wash well, coarsely chop and cook briefly in creamy soups or stews, or mix into hot mashed potatoes.

TOMATO LEAVES AND STEMS Steep for 10 minutes in hot soup or tomato sauces to add a pungent garden-scented depth of tomato flavor. Discard leaves after steeping.

TOMATO SCRAPS Place in a sieve set over a bowl, salt well and collect the pale red juices for use in gazpacho, Bloody Marys or risotto.

TURNIP, CAULIFLOWER OR RADISH LEAVES Braise in the same way as (or along with) collards, chards, mustard greens or kale.

WATERMELON SEEDS Roast and salt like pumpkinseeds.

Article courtesy of nytimes.com